Every member of the military has their own experience.

However, there are common threads that relate to leaving home, being separated, and coming back that cross almost every major conflict in U.S. history. On the home front, families deal with the absence of and fear for their loved ones. For both veterans and their families, returning home can be both welcoming and challenging. U.S. wars are mostly fought abroad, allowing many Americans distance from the personal implications. The war experience, however, remains with veterans for the rest of their lives. The implications of sending men and women to war are profound and enduring. Just as veterans and their families have served our country, society can serve them better by understanding their experiences. The legacy of war should come home for all of us.

These letters, photographs, and objects offer insight into the thoughts and emotions of veterans and their families.

“Outside of being censor for our company, I am also adjutant which all keeps me busy. I wish I could publish some of the letters. Some are pathetic, some obscene, some nonsensical, some pessimistic, and some optimistic. We must first read each letter, cut out undesirable parts, write our name on it, seal it, and put the stamp of approval on it, which is quite a bit of work.”

Uniforms Over Time

Uniforms Over Time

In a letter from 1897, local Civil War Veteran Henry H. Adams wrote, “The ties are strong between those who were together under such circumstances.” 1974.25.0145, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

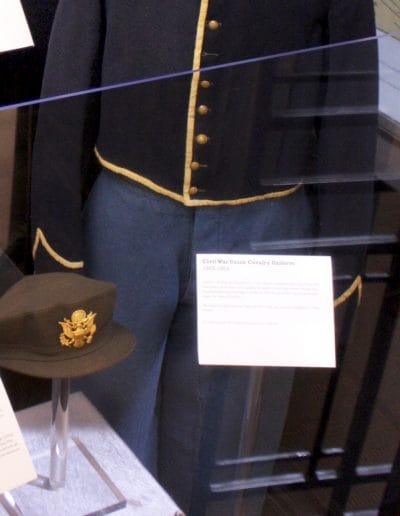

Civil War Union Cavalry Uniform, 1863-1864

Calvin H. Thomas was 16 years old in 1861 when he enlisted in the Union Army with Company C of the Sixth Ohio Cavalry. His uniform’s pants have two layers of cloth in the seat and extra padding for riding horses. 1971.20.0014A and B, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

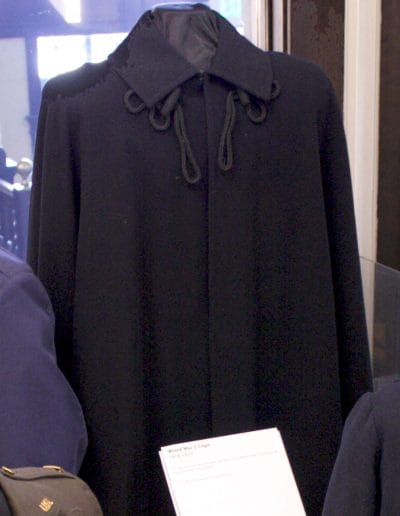

WWI Medical Cape, 1914-1918

Dr. John W. Amesse wore this wool cape while serving with the medical department of the United States Army Reserve. 1977.10.0098, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

WWII WAC Uniform, 1940s

Sue Ogata Kato served in the Women’s Auxiliary Corps in World War II. Along with 47 other Nisei women, or children born in America to Japanese immigrant parents, Sue attended the Military Intelligence Service Language School in Minnesota. 1977.53.0004.1-.2 and .0007, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

Military Medals and ID Tags

Includes: “Filii Veteranorum” Badge, Circa 1881, World War I Victory Medal, 1919, Medal Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of World War I, September 22, 1993, World War I ID Tag, 1914-1918, and Clifford Baker’s Dog Tags, 1951-1980

Air Force Dress Uniform, 1966-1973

Staff Sergeant David Widener wore this dress uniform on special occasions throughout his service. He recalls that he chose to serve in the Air Force because of the technical training opportunities it offered. 2006.103.0002A-B, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

The War Experience: Perception VS Reality

Men and women on the front lines often see things that civilians can only imagine. Can those who have not served understand the experience of war just from watching and reading media reports?

“Although most people think that they are War Conscious, are they really? So far removed from the battle fronts, can they be? You are really War Conscious when you see the airplanes, in formation, early in the morning…and see this same formation returning in the evenings. But the number is not the same! Twelve went out, nine returned…You wonder, what really did happen…You’d have to see the wounded streaming back from the front after a battle…above all, to see the light go out of men’s eyes. Young men shaking from nervous exhaustion and crying like babies. When I was in the States, War was far away, unreal. I had read, I had seen pictures, but now I know.”

Listen to the Letter

Far From Home: Wartime Separation

While military personnel are serving abroad, those at home are left to carry on their daily activities, not knowing if their loved ones will return. Serving in the military carries a price — one that is paid by both the troops and those closest to them.

“My son: you are missed in our home. There is a silence and a sadness because of your absence. Everything in the house reminds us of you. There are moments when it seems that we can hear your voice, singing your favorite songs. Your paintings, your sketches, your books, they all lie quietly where you left them upon your departure. They seem to move, impelled by invisible hands, to make more vivid, in my soul, the illusion of your presence…”

Bedtime Stories

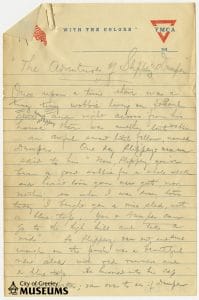

Circa 1914-1918

Click the image to enlarge

World War I split families around the world apart. Local doctor John W. Amesse served in the medical department of the U.S. Army Reserve. Throughout his service, he sent his children bedtime stories. The fantasies he came up with helped the family cope with his absence. This one is titled “The Adventures of Slippery and Dumper”.

1993.39.0314B , City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

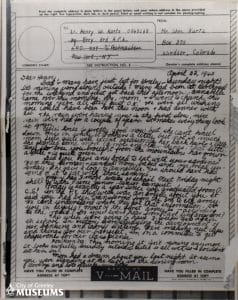

"Do you think that you will have to go to war?"

Click the image to enlarge

While Dr. John Amesse was overseas, his wife, Mary, and their two children, John and Helen, wrote him countless letters. Helen wrote this letter when she was seven years old.

“Dear father,

When are you coming home the teacher said that I would beat the whole class if they didn’t work up patty went to visit her Sunday and sed [said] that I was very good in school I stepped in the water Wednesday and got my feet wet and before I had a cold and I forgot to say that I cought [coughed] all day in school

Do you think that you will have to go to war I fell off a chair and the chair fell over on top of me you know Johns red chair and he makes such a noise with it that it makes everyone go almost crazy

From Helen Amesse”

Dr. Amesse returned to his family after the war.

1993.39.0329B, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

World War I Diary

Click the image to enlarge

John Werkheiser’s diary shows just how much he missed his loved ones while serving in World War I. Inside the front cover, he kept track of how many letters he had written to each person listed. Notice how the numbers beside both “Home” and “Jessie” (John’s wife), stop and start again where he had more room on the page. According to his tally, he wrote 50 letters home and 127 letters to his wife.

2010.61.0076 and 2010.61.0093, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

A New Normal: Adjusting to Life at Home

Coming home to “normal” life from a war zone can be a jarring experience for many troops. How they cope with this transition often depends on what happened to them while they were deployed and how they’re treated when they return. For some veterans, writing about their experiences can be therapeutic. It can help them process their memories and emotions in new ways, help explain their experiences to civilians, and even connect them to other veterans.

“It just seemed like the world had come it an end. It was completely different. I stayed on the farm with the folks for one year. But I just couldn’t hack it. It wasn’t what I had been trained for.”

Enduring Loss: The Cost of War

No other hardship in a time of war can compare to losing a family member or friend, and the grief is sometimes so overwhelming that it can take months, years, and even decades to say “good-bye.”

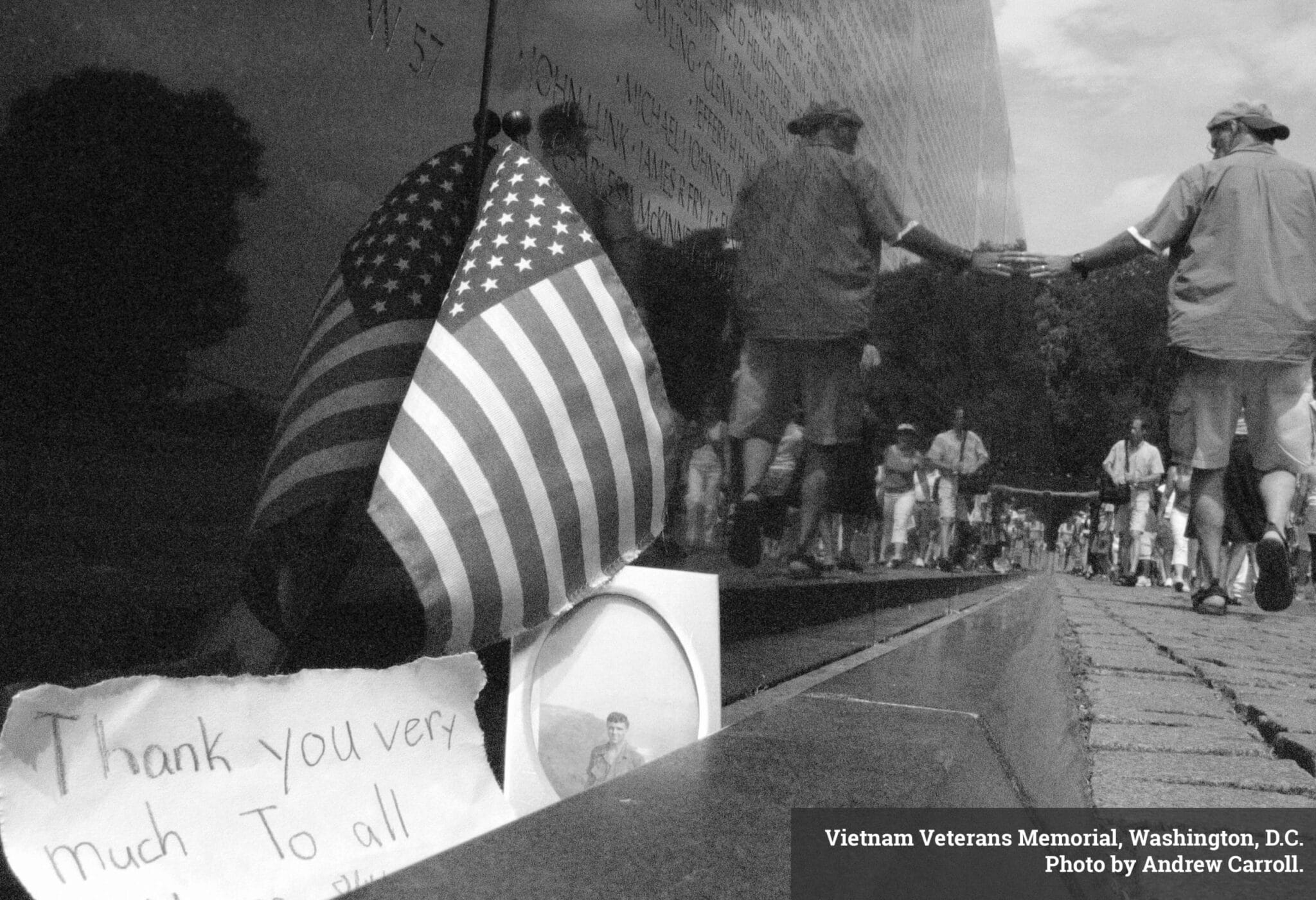

“The things that I am going to say in this letter are about twenty years and a whole lifetime late, but maybe that won’t matter once they’ve been said. A lot of the guys who were there say they feel like they lost something in-country. I know what I lost. I’ve always said that when you died, it was like killing the other half of myself. Maybe that’s not necessarily true. What I did lose was youth. . .all of the idealism, trust, self-confidence, and personal power that we had, either inside or drilled into us. I’m scared now, most of the time, and I hurt a lot. What happened to us, has cost me a life as much as it’s cost you yours. I’ve never been able to get close to anyone since you died. My wife, step-daughter, my son. I live in the past, ‘cause today hurts too much. I want out of the past. The war is over, I need my war to be over too. I never got to say goodbye. I’ve come to this monument to have a little memorial service and to say goodbye and to let you go. I’ll never forget you, don’t worry about that. Goodbye, John.”

Listen to the Letter

“May we remember also that in war, even victory is costly—not so costly as defeat, but heart-breakingly costly, of which those who have been deprived of the association of their loved ones need no day of special reminder—for them every day brings it[s] own reminder.”

Army Air Force Uniform

Click the image to enlarge

Preston Day graduated from Kersey High School in 1935 and chose to enlist in the Army Air Force as an aviation cadet in May of 1941, sent to advanced training in California, promoted to second lieutenant in September 1942. At 5:15pm on October 29, 1942, he was killed when his plane crashed into a field while training in California.

Preston’s mother, Jessie Day, donated this uniform to the museum in 1968. Our records state that it was “very precious” to her and that “she wanted it well cared for”.

3041.0001.1A-B, .0001.2, .0001.3, and .0003, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

Footlocker Keepsakes

Click the image to enlarge

Henry “Hank” Kurtz graduated from Windsor High School in 1939 and enrolled as a chemistry major at Colorado State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now Colorado State University). He decided to enlist in the Army in the fall of 1942. He attended basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, then went to armored officers’ candidate school at Fort Knox, Kentucky. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant on April 22, 1944. In January of 1945, he was deployed to Europe and served as a tank operator.

Henry was killed on April 10, 1945, when his tank exploded in Germany. These items were discovered in Lieutenant Henry Kurtz’ footlocker after his death. They were sent to his family along with his other personal effects.

2012.116.0049, and 2012.116.0056.2, .7, .14, .18, .19, and .20, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

Letter Written to a Soldier after His Death

Click the image to enlarge

It took several weeks for the military to notify Henry Kurtz’ family of his death. They were first told that he was missing in action, but were informed a few weeks later that he had been killed on April 10, 1945. They had written several letters to him before learning of his death.

In this eerie letter from April 22nd, Henry’s sister Ruth wrote, “Mom had a dream about you last night. It seems you were standing at the table in the dining room.” This wasn’t the first time that Henry’s mother had reported having “premonitions” of his death.

In a later interview, Ruth recalled that even before he went to war, “We were worried about him getting killed, because my mother was convinced in advance that he was going to die in the war. She had a premonition and so this was constantly in the back of our minds. She would repeat this every so often and make sure we didn’t forget to pray for Henry and help him out any way we could.”

2004.36.0142.1-.2, City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection

Reflections: Before and After

Every veteran has a different individual experience in war and a different reaction to coming home. While some choose not to talk or write about it, others find it beneficial to reflect on their service and how it has, and will, affect them. Along with the physical wounds of war, there are often emotional scars as well. Although invisible, they can prove just as lasting.

“We have these reunions. We all get together and reminisce. It’s just wonderful…It’s been about fifteen years, I believe. In the start we had them every five years, but now we have them every year. They’re passing away and it’s getting smaller. If we had them every five years, there wouldn’t be anybody associated with it. But now every year we get together.”

A New Mission: Coming Home

“Those of us coming back from Iraq or Afghanistan are not looking for sympathy. We might be reluctant at first to talk about what we’ve been through, good or bad, and some troops might never be able to open up, which is certainly their right… But I hope that those who need to will reach out, and it’s helpful knowing that there are people who care about us and are at least making an effort to understand. Your support has made this journey an incredible one for me, and I couldn’t have gone through it alone. Thanks for joining me—and thanks, above all, for listening.”

Listen to the Letter

Honoring Local Heroes: The Weld County Veterans Memorial

Located in the southwest corner of Bittersweet Park, the Weld County Veterans Memorial features statues and stone pillars with information about each conflict in our shared history.

Each statue and symbol included on the monument was chosen deliberately, from the eagle to the stone pillars and the statue at the monument’s center.

The bronze statue standing in the center of the monument represents Ault veteran Private Joseph P. Martinez. He was the first Hispanic American to be awarded a Medal of Honor in World War II. Learn more about Private Martinez >

The monument’s creators update the lists of local veterans frequently, as research reveals new names.

Impact of the Memorial

Audio Transcript: Impact of the Memorial by Rick Wertz

Interviewer: Tell me about how you got interested. How did you hear about the design—I think it was a contest wasn’t it, for the Weld County? How did that all come about?

Rick Wertz: Well, I was a salesperson for Norman’s Memorial, and the Gulf War – first Gulf War – was underway and when we invaded Kuwait, we was there for just a short time. And then President Bush brought everybody out, and kind of called for a- a win I guess, you know. So along that way there was an article in the Greeley Tribune. There was a committee which included Arland Rutz. It was Gary Park and Jerry Parks. They was looking for a design concept to build a monument for them. And they were going to replace the monument in Lincoln Park. I went to their meeting and they kind of gave me the criteria that they was looking for. And they was looking for a monument that would pay tribute to all Weld County veterans, and something that could be up for, you know, that was brought up to date. And with a gentleman that worked along with me at Norman’s Memorial, we came up with this concept. And that was the four walls in about a 20-foot radius and with an eagle on top and the history of the Spanish- all the wars dating back to when Weld County was first certified as a county. And so, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, Pacific and European theaters, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf. The theory kind of behind not doing anything when we built it was to show the public that the people that built it didn’t want the recognition. This monument was built for veterans only, to recognize the veterans. And my mother, God rest her soul, told me before she died, she says, “Rick, why didn’t you guys ever put your name up there?” She says, “Don’t you think that someday ,some may want to know who built this? Maybe your kids or grandkids or some guys that help you, their grandkids?” And so, I had a little change of heart and surrendered, and so after the lights, that’s the next…

Interviewer: The next project?

Wertz: The next big, big project.

Wertz, continued: When you’d see a World War II guy or a Korean War guy, they’re getting along in age, and they kind of walk up with us, walk around. Some of them sit down. Some of them look at the history, look for their name. And you look at them leaving and they’ll start wiping their eyes. You know that you’ve hit a nerve there. And the second one is, I’ve had Vietnam veterans tell me that they’ve never had- had closure till they’d been there. All those years, never had closure.

This virtual exhibit contains text, images, and audio provided by the City of Greeley Museums and Exhibit Envoy.

War Comes Home: The Legacy is a partnership between Cal Humanities, the California State Library and Exhibit Envoy. The exhibition is based on the collection of the Center for American War Letters (CAWL) and curated by Andrew Carroll, the Director of CAWL, and John Benitz, Professor, Chapman University. It is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the BayTree Fund, The Whitman Fund, and the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian.